I have been working as a professional glacier guide for the past three summers. Through my work I have learned the importance of preparation for outings. Clothing, technical gear, route information and timing are crucial elements that must come together for any successful day. When taking clients out, making a mistake is not an option. While triple checking is entirely necessary for a guiding business, on my personal days I prefer to leave a few things unplanned for the sake of excitement.

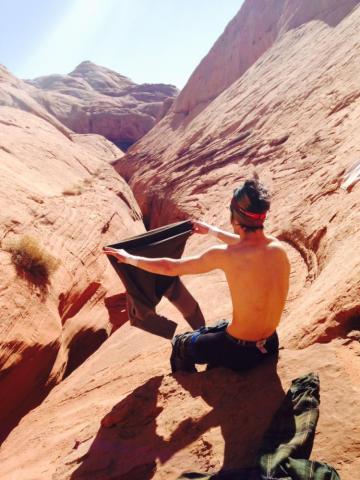

On my most recent trip to the Utah desert, my roommate Gefell and I descended a slot canyon named Shenanigans, with a particular lack of planning. Slot canyons, narrow gorges carved into sandstone by millennia of flash floods, are known for being destructive of gear and clothing. Since we had already paid for gas to get to Utah, Gefell and I chose to wear only cotton because it is cheaper to replace than its synthetic counterparts.

Technical slot canyons, like Shenanigans, often require several rappels over unclimbable smooth rock faces. After each rappel you pull your rope, thereby committing yourself to continuing down the canyon towards the exit. We had a great start, albeit late in the day, and easily found the entrance to the canyon and completed the first rappel. We pulled the rope; no going back.

Snow early in the week had been followed by warm weather. The resulting runoff had found its way into the canyons and as we descended deeper in the slot we encountered pools of standing water. We soon came to a drop into water with no way to stem over the top. Sand had turned the water to the color of rust, preventing us from gauging the depth. We guessed it to be at most a foot deep. Geffell removed his shoes and socks, throwing them to dry ground on the other side of the pool. He rolled up his pant legs and handed me his pack, then carefully slipped in. He sunk to his chest. “Yup, it’s deep,” he gasped and then swam to the other side.

“Good thing we brought extra layers in a dry bag,” I said as I emerged a minute later, also soaked. I picked up the dry bag that I had hucked across. “Never mind,” I added, “all of our clothes are soaked.” The platypus water bottle that I strategically packed with our dry layers had exploded. We now had only one liter of water and as well as several heavy, soggy, useless cotton layers.

While putting my wet socks on I realized that my previously injured big toenail had decided it was a great time to fall off. I had injured it skiing several months earlier and knew its time was coming, but for it to happen now felt like adding insult to injury.

Above us on the desert plateau it was 60 degrees by midday. However, the sunlight could not reach deep into the confines of our canyon. Deep in the shadows, it felt closer to 40 degrees. We moved as fast as possible to help keep warm.

The canyon twisted its way down and down. We worked our way through hundreds of yards where the walls were so narrow you could not turn your head from one side to the other. The only way to advance was an awkward sideways shuffle, holding your bag behind you. Often it was necessary to suck in our guts to move past sections. At 6-foot, 160 pounds, I am much bigger than my roommate and, therefore, had the most trouble squeezing through these tight spots.

After severals hours of panting, squeezing and cursing we came upon what our professional guidebook (a trip blog I found on my phone) described as “the grim crawl of death”. It was a narrow ledge with a two-foot high ceiling. It sloped steeply sideways towards a 50-foot drop to the canyon floor. There was no anchor to rappel from; the only way to continue was to army crawl across the ledge and then down climb a series of chalkstones (boulders wedged between the canyon walls). I drew the short straw and inched my way across headfirst, while my legs slowly swung towards the edge of the ledge. I found it to be even grimmer than the name suggested.

“Wow,” Gefell said, “That was sketchy even for you.” He backed up a few steps, then lunged forward and slid across the ledge, much like you would across the hood of a freshly waxed 1967 Chevy Camaro. Gefell has a way of making hard things seem effortless. I silently cursed his grace.

We moved quickly through the final narrows and found ourselves at the end of the canyon. The walls continued forward for a hundred feet, but the floor dropped away into nothingness. We made two rappels. The second was free hanging and ended in another pool of ice-cold water. Next to the pool was a pair of torn jeans and the remnants of a fire. Apparently we weren’t the first to get cold descending Shenanigans.

Where the slot canyon ended, a beautiful gorge began. The valley bottom was teaming with riparian vegetation, and the red rock walls rose vertically over 500 feet on either side. Our guide blog described the exit out of the gorge as “a thousand feet of chossy climbing, that looks difficult at the bottom and impossible at the top.” We had no problem spotting the exit a few miles down canyon, and had a great time monkeying our way through the crumbly sandstone to the top. Once we reached the rim it was an uneventful, albeit miserable, five mile slog back to the car. We even made it back before dark.

Although this trip went mostly according to plan, I want to highlight that it only takes one small mishap to turn an outing into an adventure. Temperatures at night during our trip dropped consistently below freezing. Had we been held up for any reason in the slot, it would have been a seriously rough night given our lack of dry clothing.

All of the clothes I wore that day are long gone, due to the innumerable holes that were worn into them. The pack I took with me has since been warranteed. Despite this, the next time I go canyoneering I will be taking clothes that keep me warm when wet, regardless of the costs to replace them.